MONDAY, 11 MARCH 2024 AT REGENT’S UNIVERSITY, LONDON

BY SIMONE THEISS

I. The Background:

1. Some of you might remember that my Amnesty Group Westminster Bayswater organised in 2019 together with “Exiled Writers Ink” an event at the Poetry Café in London. It was called “Words for the Silenced“. It focussed on four prisoners of conscience who were in prison for their words and who wrote poetry: Ahmed Mansoor (UAE), Ashraf Fayadh (Saudi Arabia), Galal El-Behairy (Egypt) and Nedim Türfent (Turkey). It was a great event. The Poetry Café was packed and we were delighted that we were able to raise awareness for these prisoners and their poetry.

2. Five years later, we thought it is high time to organise another event. This time the event was co-organised by Exiled Writers Ink, Amnesty Westminster Bayswater and Amnesty Mayfair Soho in collaboration with the Regent’s University Liberal Studies Department.

3. This time we spoke about prisoners from five countries: United Arab Emirates, India, Iran, Egypt and Turkey.

The prisoners were:

- Ahmed Mansoor (United Arab Emirates)

- Varavara Rao (India)

- Mahvash Sabet Shariari (Iran)

- Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee (Iran)

- Galal El-Behairy (Egypt)

- Alaa Abd El-Fattah (Egypt)

- İlhan Sami Çomak (Turkey)

II. The Event

1. Introduction

With events like this, I am always wondering whether we will have an audience, whether we shared the information about it with enough people, whether people are actually interested enough in human rights and poetry to come along.

This was the case five years ago for our “Words for the Silenced” event at the Poetry Café and it was the same this time at the Regent’s University. Last time the Poetry Café was packed, therefore the expectations were high for this year.

Fortunately, we were not disappointed. We realised quickly that the room at Regent’s University did not have enough chairs. We had to add chairs twice and still had a couple of people standing.

We had 15 speakers and readers and we think there were about 70 people in the audience. I am grateful to everyone who shared the word about the event and of course to everyone who actually came and participated as a speaker or as part of the audience.

The event had two co-presenters: Catherine Davidson. She is a member of the board of Exiled Writers Ink and teaches Literature & Creative Writing at Regent’s University. Catherine is also a novelist, poet and translator. I was the second co-presenter.

At the beginning of the event, we introduced the event from the point of view of literature (Catherine) and human rights (me). We also explained why we decided to have this event in the middle of March. There are a number of good reasons for that, because there were three significant dates very close to the event: On 5 March was the sixth anniversary of the arrest of Galal El-Behairy, on 8 March is the birthday of İlhan Sami Çomak and on 20 March was the seventh anniversary of the arrest of Ahmed Mansoor.

We also asked people to get active. We had prepared letters to the authorities in support of seven prisoners and also messages to Varavara Rao and to İlhan Sami Çomak who are both able to receive messages themselves. We asked people to sign these letters during the interval and after the event. Catherine also asked people to contribute to a poem. I will share more information about this creative contribution later.

2. United Arab Emirates: Ahmed Mansoor

The event started with a section about Ahmed Mansoor, a blogger, poet, engineer and human rights activist from the United Arab Emirates and more specifically with a film clip from Manu Luksch’s film about Ahmed Mansoor. Manu Luksch is an Austrian artist, film maker and researcher. She has been working on a film about Ahmed Mansoor for some time. If I understand it correctly, the bulk of it has been filmed, but there is still a lot of work to do. The film clip contained an excerpt of an interview with him. He speaks about his childhood in a small village and how the United Arab Emirates have developed since then. He mentions that he was involved in literature and also emphasises that this is the reason why freedom of expression is so important for him. He also shares with the audience the first demonstration he participated in. He was in primary school and he, his classmates and the teacher demonstrated and demanded electricity to be brought to their village.

After the video clip Bill Law spoke about Ahmed Mansoor. Bill Law is the editor of Arab Digest and an award-winning journalist, he reports extensively from the Middle East and North Africa (inter alia for BBC). He knows Ahmed Mansoor personally. He spoke about him and read an English translation of the poem “What are all the stars for” from the poetry collection “Beyond Failure”.

Melanie Gingell was the next speaker. She is a barrister and human rights activist and inter alia a member of the Advisory Board of the Gulf Centre for Human Right to whom also Ahmed Mansoor belongs to. Also she knows Ahmed Mansoor personally. She read his poem “Final Choice” (from the same poetry collection).

The last speaker about Ahmed Mansoor was Drewery Dyke. He is chairperson of the UK charity Rights Realization Centre and the International Partnerships Contact Point for Salam for Democracy and Human Rights. He also used to work for almost 10 years as researcher with Amnesty International (focusing on Iran, Afghanistan and Arab Gulf states). Also Drewery Dyke knows Ahmed Mansoor personally. He spoke about his impression of Ahmed and read the poem “Boredom” which is also from the poetry collection “Beyond Failure”.

Ahmed Mansoor’s poetry collection “Beyond Failure” was published in 2007 in Arabic. This collection was sadly never published in an English translation, but you can find English translations of some of the poems in my blog posts Ahmed Mansoor – a poet and in Ahmed Mansoor – another birthday in prison.

3. India: Varavara Rao

The next section was dedicated to the Indian poet, teacher, journalist, literary critic and activist Varavara Rao.

Our speaker about Varavara Rao was Lotika Singha. She is an activist who campaigns for freeing political prisoners, in particular in the context of India, her country of birth. She met Varavara Rao several times and gave the audience a detailed and engaging introduction to this poet and activist.

As mentioned Catherine Davidson, my co-host, teaches Literature & Creative Writing at Regent’s University. She asked some of her students to get involved. It was a particular pleasure to have four acting students reading most of the poetry. One of the students was Rajveer Dogra Dogra. He is himself from India and is studying Acting for Stage and Screen at Regent’s University London. He read three poems by Varavara Rao: “Yes, He Too is a Man”, “Oh Enemy” and a new poem. Varavara Rao is currently not in prison, but was released on bail. Lotika Singha informed Varavara Rao before the event that the event will take place and asked him whether he had any message for the audience. He asked her to also include his latest poems. A friend of his translated it for the event in the last two days before the event.

If you want to know more about Varavara Rao and in particular read more of his poetry, then you can get the book “Varavara Rao: A Life in Poetry” which was published last year by Penguin India. It is his first-ever poetry collection in English and includes translations of poems from sixteen books that he has published throughout his life.

4. Iran: Mahvash Sabet Shariari and Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee

The final section in the first half of the event was dedicated to two remarkable Iranian women: Mahvash Sabet and Golrokh Iraee. Mahvash Sabet is a member of the Baha’i. She was a school teacher and school principal before her dismissal. She then played a key role in the Baha’i as a community leader. She is also a poet. Golrokh Iraee is a writer, poet and human rights activist.

It was a great pleasure and great honour to have Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe as a speaker about these women. I am sure most of you have heard about Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe. She was held hostage in Iran for 6 years, most of which was spent in Evin prison, in the women’s political ward. Since her release she has campaigned for a number of her former cellmates. She was in the same prison ward as Mahvash Sabet and Golrokh Iraee. I have been campaigning for Golrokh and also for Mavash for a long time and I thought it was absolutely fascinating to listen to Nazanin speaking about these two women and giving a personal insight into them.

Nazanin finished her part by reading a poem by Mahvash Sabet which is called “For Narges” and which she wrote in support of Narges Mohammadi who received last year the Nobel Peace Prize. Nazanin gave a short introduction before she read the poem and it is fascinating that she told us that they had been joking around that Narges might win the Nobel Peace Prize, but then it became a reality.

The next speaker was Nazanin’s husband Richard Ratcliffe. He had been campaigning tirelessly for years for the release of his wife. Since her release, he supports other hostage families, but mainly works as an accountant in London. He read Mahvash Sabet’s poem “The Star”. Before he read the poem he shared a moving recollection. Six years ago Exiled Writers Ink organised their first Words for the Silenced Event which focussed on Iran. It showed in the first half a play about Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe. The second half featured poems written by Iranian poets. This half included poems which Richard had received from Evin prison and which were written by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, Narges Mohammadi, Nasim Bagheri and Mahvash Sabet Shariari. He remembers how different the situation was for him then when he was full of campaigning, but also angry compared to now and encourages everyone to keep campaigning, because it can lead to change.

After Richard Ratcliffe’s reading, four acting students read three poems by Golrokh Iraee and three more poems by Mahvash Sabet.

The first poem was Golrokh Iraee’s poem: “Couples in Prison”. Golrokh wrote the poem reflecting on the time when she and her husband Arash Sadeghi were both in prison “And a wall between us / As deep as a hand span“.

The next poem was Golrokh Iraee’s poem: “Standing Straight”. This poem was read by Ali Razzaq who is also an acting student at Regent’s University.

The last poem by Golrokh Iraee was “Counting Up, Counting Down” which was read by Rajveer Dogra Dogra.

This was followed by another acting student who read two of Mahvash Sabet’s poems: “The Great Outdoors” and “Lights Out”.

This part of the event ended with Ali Razzaq reading Mahvash Sabet’s poem “Floodgates”.

A collection of Mahvash Sabet’s poems in English translation was published in 2013. The book is called “Prison Poems” and contains poems which were written when she served the sentence from the 2010 judgement. If you are looking for Golrokh Iraee’s poems, it is more difficult. There is sadly no book of her poems published in English translation. However, you can find the English translation of some of her poems on this website.

5. Egypt: Galal El-Behairy and Alaa Abd El-Fattah

The first section after the interval was about two prisoners in Egypt: Galal El-Behairy and Alaa Abd El-Fattah. Galal El-Behairy is an Egyptian poet and lyricist. He was also included in our “Words for the Silenced” five years ago. Alaa Abd El-Fattah is a well-known British-Egyptian human rights activist and blogger.

I spoke at the beginning of this section and gave a short introduction about the section, but in particular about Galal El-Behairy. There is no video clip of my introduction, but you can read his story in the previous blog post. I read in particular an excerpt from Galal’s letter which he wrote last year to mark the fifth anniversary of his arrest. I included the excerpt also in the blog post. As mentioned there he wrote last year also a new poem with the title In My Silence is My Death. In this poem he reflects on his situation in prison. The Egyptian rock musician Ramy Essam sings many songs with texts by Galal El-Behairy and is a strong supporter of the campaign for Galal’s freedom. He wrote last year a new song which set Galal’s poem to music and which was released at the end of March 2023. The song is called Fiskooti Mooti (In My Silence Is My Death). We showed the video clip of this song in our event:

After the song, two acting students from Regent’s University read Galal El-Behairy’s poem “I Have a Date with Tomorrow”.

They first read in Arabic:

… and then the English translation of the poem:

Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s family strongly advocates for him and for his release. We invited his sister Mona Seif who lives in London. She would have loved to come in person but she recently gave birth to a daughter and evening engagements with a small child are – for obvious reasons – difficult. However we were fortunate that Mona sent us an engaging video clip which we showed.

Alaa Abd El-Fattah’ does not write poetry, but he is a blogger and wrote many texts over the years. We were delighted to have Anna Sullivan to read Alaa’s text: “Half an Hour With Khalid”. Anna Sullivan is an actor, director and teacher who has worked in television, film and radio. The text “Half an With Khalid” was written in 2011. Alaa was in detention when his son Khalid was born.

If you want to read more of Galal El-Behairy’s poems, then please have a look at Ramy Essam’s website. You can find there seven poems which Galal wrote in the last years while being in prison. If you want to read Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s text “Half an Hour With Khalid” and other texts, then you can do so in the book “You Have Not Yet Been Defeated” which contains selected works from 2011 until 2021 and was published in October 2021 at Fitzcarraldo Publishing House.

7. Turkey: İlhan Sami Çomak

The final part of the evening was dedicated to İlhan Sami Çomak. İlhan Sami Çomak is a Kurdish poet who has spent almost thirty years in prison in Turkey. Our speaker for him was Caroline Stockford. She is a poet, writer, translator and human rights advocate. She has been running the Ilhan Sami Comak campaign for PEN Norway since 2020.

Caroline gave an excellent and moving overview over İlhan Sami Çomak and his current situation. She also touched on campaigns for him which often involved solidarity through poetry writing. In her talk she quoted one of İlhan’s recent letters which he wrote marking his birthday on 8 March, hopefully his last birthday in prison. Even more special was that she had a message from İlhan for us. She told him about this event and he sent the following message:

“Until today poetry has always been my home, my heaven. I have always taken refuge in it from the cruelty of prison. Now, in a very short time, I will be a free man and this time I will move my poetry heaven to the world so that I can take shelter in it whenever necessary.

I have always been very grateful to Amnesty International for being the voice of oppressed people around the world. Knowing the value of this very well as a poet who spent decades of his life in oppression, I would like to say that all their efforts are highly appreciated. Now being the subject matter of their meeting gives me even extra strength. I am excited that they heard my voice and the voice of my poetry. I am even stronger with the energy which I will find from this now and I thank you all very much for this.”.

Caroline Stockford’s talk was followed by the reading of four of İlhan Sami Çomak’s poems by the acting students.

First, Ali Razzaq read his poem: “I Came to You, Life”.

The next poem which Ali Razzaq read was İlhan Sami Çomak’s poem “Let Us Not Speak”.

The third poem was “Things That Are Not Here” by İlhan Sami Çomak.

The final reading of the evening was a poem with a very appropriate title for an evening dedicated to poetry and human rights: “What Good Is Reading Poetry?”

As mentioned in the previous blog post, İlhan Sami Çomak published over the years ten books: nine poetry collections and his autobiography. However, all these books are published in Turkish. There is one book available in English. It is called “Separated From the Sun“. It is a collection of poems by İlhan Sami Çomak. Many are written as responses to poems which were written by poets from all over the world in support of him. The poems were translated by our speaker, Caroline Stockford, and the book was edited by her.

III. Final Remarks

1. Letter writing

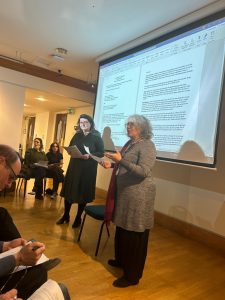

As mentioned at the beginning of the post, we had prepared letters to the authorities in support of all seven prisoners and in addition messages directly to Varavara Rao and to İlhan Sami Çomak.

We asked people to sign letters and cards during the interval and at the end of the event.

This action was very successful. We had altogether almost forty letters with signatures and a few cards. Many of them had several signatures and we think we had altogether collected more than 100 signatures. Thank you so much to everyone who joined in and who signed a letter to the authorities or a message to Varavara Rao and to İlhan Sami Çomak.

2. A Poem in Solidarity

I mentioned in the context of İlhan Sami Çomak how poetry can be a sign and a tool of solidarity.

Catherine Davidson had the idea to not only have solidarity in the writing of letters (something typical for Amnesty International), but also give solidarity in the way of the writing of a poem. She asked the audience before the final section about İlhan Sami Çomak to take a blank card and write down on the one side phrases from his poems which the person found particularly memorable or moving and on the back of the card a reaction to these phrases or words.

At the end of the evening she collected all the cards, took them home and wrote a poem based on these impulses from the audience.

Catherine says that

“[t]he result was a beautiful mosaic, a conversation across time and space, between the poet trapped in his solitary cell, and each of us in that room, intimately linked through his words.”

I think this is a really wonderful and creative way to show solidarity with poets who are in prison. Catherine wrote a post on Medium from which also this quote was taken. She shares in the post her impressions and reflections on the event and shares insights in her process of writing a poem in solidarity. The post also contains the final product, her wonderful poem “Hope and Courage: A Collective Poem for İlhan Çomak”.

Hope and Courage: A Collective Poem for İlhan Çomak

Let us whisper. Let us speak.

Taking shelter inside each other’s thoughts.

Sing songs, throw stones.

Challenge us with beautiful truths.

The language of leaves, the sound of colours

Rustle blue tranquillity, spirit gliding in the breeze.

The fluid beauty of butterflies: Subtle

surfaces of moth wings, pen upon the wind.

Bars can never constrain feelings.

Open the window, the door. Let words spring.

I am the only one, but I am one.

Whispers of freedom combine to a roar.

Coming back to the world, this same sun

kissed bare shoulders, will kiss again tired lids.

Deep and faraway, a star is flickering.

Dear Brother, you kept faith with the world.

Look: sparrows opened the sky, took off in great numbers.

Among them the unshackled minds of poets.

Think of the river. Dream of a journey,

Shooting rapids to arrive in the broad delta.

Let us use this stick to walk in the hills.

Let us laugh. All joy will soon be yours.

3. What next?

As always I want to ask you, not to forget these poets, writers and prisoners of conscience. Please share the information about them and please share their poems.

You can find all the video clips which are included in this post on YouTube. They are all on the YouTube channel of Amnesty Westminster Bayswater (apart from Ramy Essam’s song which is on his own YouTube channel). You find the individual clips under videos or shorts, depending on the length of the clip. I also made playlist “Words for the Silenced” with all clips. Please share the clips and share the playlist.

I want to close the post with this wonderful photo of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Richard Ratcliffe and the four acting students who read most of the poems.

I wish that some time soon we are also able to have photos with the poets and prisoners about whom we spoke in the event and whose work we shared – free, able to travel and that we can listen to them reading their own works.